Video

On Film Directors and Styles.

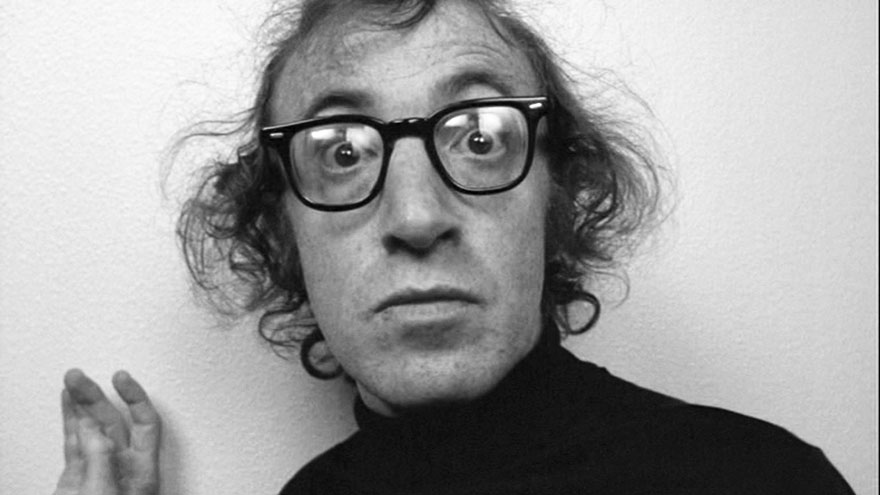

According to Woody Allen there are two kinds of film directors: “the ones who have it, and the ones who don’t.”

It is well-known that there are two other kinds of movie directors: the ones who write their own material, like Tarantino, and the ones who adapt, like Alfred Hitchcock or Steven Spielberg. The Coen brothers are crystal clear on this: “We are willing to write for other people, but we would not direct a script that has been written by somebody else.” To Scorsese “the script is the most important thing, but it is not everything. What matters is the visual interpretation of what you have on paper.”

John Boorman believes that “directing is really about writing, and all serious directors write.” But there are extremely serious directors who do not work with scripts, like Wong Kar-Wai. “I write as a director, not as a writer, so I write with images. I start with a lot of ideas but the story is never clear. I know what I don’t want, but I don’t know what I want. The shooting process is the way for me to find all the answers. Sometimes I find them on the set, sometimes during the editing, sometimes three months after the first screening.”

Martin Scorsese has, as usual, something interesting to say about the difference between being a director and a being filmmaker. According to him, a director is “someone who only interprets the script and transforms it from words into images.” A filmmaker is “someone who is able to turn his own or somebody else’s material and still manage to have a personal vision come through.”

From a more technical perspective, we have directors who arrive to the set knowing exactly what they are going to shoot, with how many cameras and which lenses (like the Coen Brothers) and there are others who arrive with simply an idea and then follow their gut instincts (like Woody Allen).

When it comes to directing styles there are also antagonistic approaches. Some directors watch the actors rehearse and then decide with their DP where the camera should be, and how many shots will be needed. Fellini is a prime example of this approach. Scorsese disagrees: “you need to know where you are going and you need to have it on paper.” But some directors do the exact opposite. They walk around the set, decide where the camera goes, where the action will take place, and then ask the actors to accommodate.

Wim Wenders used to spend “every evening painstakingly preparing the next day’s shoot, making detailed drawings mimicking storyboards.” After “Paris, Texas” he has taken the opposite approach, “finding the scene construction in the action, and arriving on set without any preconceived ideas about the shots, and only deciding where to place the camera after working with the actors.”

There are some filmmakers who prefer to edit “in the camera,” such as Clint Eastwood or Hitchcock. Others, such as David Fincher, have no problem shooting 50 takes of a single scene and then figuring it all out later in the editing room over the course of months or even years. Woody Allen’s take on this is “it’s a grave error to start shooting a film with a script that is weak or not ready and think, “I’ll fix it on the set or in the editing room.’”

I could probably add two additional kinds of directors: the ones who make films because they have something to say, and the ones who make movies to find out what they have to say, but that would be a whole different article!